The Simple Riddle That Shows How Your Brain Has Two "Minds"

Let’s start with a quick puzzle, made famous by the psychologist and Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman. Read it and answer as fast as you can:

A baseball bat and a ball cost $1.10 together.

The bat costs $1 more than the ball.

How much does the ball cost?

If you’re like most people—including students at top universities like Harvard and Princeton—an answer popped into your head almost instantly: 10 cents.

This answer is intuitive, appealing, and completely wrong.

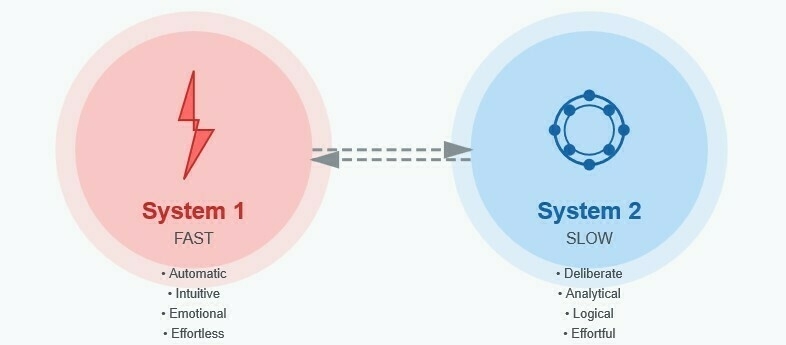

This little problem is so powerful not because it’s a trick, but because it perfectly reveals a fundamental division in how we think. Our brains operate with two distinct “systems” that constantly shape our perceptions, judgments, and decisions. Understanding them is the first step to figuring out why we do the things we do.

Meet System 1: Your Brain’s Autopilot

The fast, incorrect answer to the puzzle comes from what Daniel Kahneman, in his groundbreaking book Thinking, Fast and Slow, calls System 1. This is the fast, intuitive, and automatic part of your mind. Author Phil Barden calls it our mental “autopilot” in his book Decoded.

This system is our default setting. It runs in the background, handling most of our day-to-day tasks without any conscious effort. It’s the system that lets you instinctively finish the sentence “bread and…”, immediately know you prefer coffee to tea, or feel a flash of unease when someone’s friendly words don’t match their tense expression.

System 1 is a product of our evolution—a brilliant machine for making split-second judgments that kept our ancestors alive and helps us navigate modern life without becoming overwhelmed. But as smart as this autopilot is, it has biases and makes predictable errors, especially when it runs into a problem about a bat and a ball. To see why, we need to wake up its slow, careful supervisor.

Waking Up System 2: The Deliberate Thinker

So, what is the right answer? The ball costs 5 cents.

($0.05 Ball) + ($1.05 Bat) = $1.10

Figuring this out requires engaging what Kahneman calls System 2. This is the slow, effortful, and conscious part of our mind. If System 1 is the autopilot, System 2 is the pilot who has to be deliberately woken up to take the controls.

Engaging System 2 takes real attention and is mentally draining. It’s the mental muscle you use when you’re parallel parking on a crowded street, filling out tax forms, or trying to assemble IKEA furniture. Think of how exhausted you feel after a long meeting that required your full focus—that’s your System 2 telling you it’s out of fuel.

Because it’s lazy, System 2 often just goes along with the first suggestion System 1 offers. This is why the “10 cents” answer is so common. Our autopilot offers a plausible shortcut, and our conscious pilot doesn’t bother to double-check the math.

The Assistant and the Manager: How They Work Together

Our mental life is basically a collaboration—and sometimes a conflict—between an impulsive assistant (System 1) and a lazy manager (System 2).

System 1 is always on, generating suggestions, feelings, and intuitions. The effortful System 2 is supposed to act as the supervisor, which can approve, adjust, or block the ideas from System 1. But since System 2 would rather not work too hard, it often just signs off on whatever System 1 puts on its desk.

This explains why we so often jump to conclusions. Kahneman calls this tendency WYSIATI: What You See Is All There Is. System 1 is built to create the most sensible story it can using only the information that’s immediately available. It doesn’t stop to ask, “Is there something important I’m missing?” It just weaves a coherent story from the pieces it has.

As Kahneman explains, the quality of the information is less important than how well the story fits together.

“The measure of success for System 1 is the coherence of the story it manages to create. The amount and quality of the data on which the story is based are largely irrelevant. When information is scarce, which is a common occurrence, System 1 operates as a machine for jumping to conclusions.”

— Thinking, Fast and Slow, Daniel Kahneman

So What? The Link to Behavioral Economics

This dual-system idea is at the heart of behavioral economics. Traditional economic theory assumes that people are perfectly rational decision-makers—what Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein call an “Econ” in their book Nudge. This “Econ” is a fictional character who thinks only with the pure logic of System 2.

Behavioral economics, on the other hand, studies real “Humans”—people who are guided (and often misguided) by both systems. Our reliance on the fast, error-prone System 1 leads to predictable biases in our judgment.

For example, have you ever wondered why you prefer one brand over another, even if they’re identical? This is often due to the Framing Effect. How information is presented can dramatically change our choices. People react more positively to ground beef described as “90% fat-free” than to the exact same product labeled “10% fat." The first frame feels healthy, triggering a positive response from System 1. The second highlights “fat,” triggering a negative one. An “Econ” would know they’re identical, but for a real “Human,” the feeling the frame creates matters more than the facts.

Conclusion: What This Means for Marketers

The simple truth is that we aren’t the purely rational beings we like to think we are. Our choices and beliefs are constantly being shaped by the silent, automatic work of our intuitive System 1, with only occasional interventions from our deliberate System 2.

For marketers, this understanding is everything. Your customers aren’t carefully weighing every feature and benefit—they’re running on autopilot most of the time. This means the way you frame your message, the emotions you trigger, and the story you tell matter far more than you might think. That “90% fat-free” vs “10% fat” example? That’s not just a fun psychology fact—it’s a blueprint for how small changes in presentation can dramatically shift behavior.

The implications are clear: if you want to influence decisions, you need to work with System 1, not against it. Make your message feel intuitive and effortless. Use familiar patterns. Trigger positive associations. Remove friction. Because when you force people to think too hard (waking up their lazy System 2), you’ve often already lost them.

But here’s the ethical part: recognizing this doesn’t mean manipulating people—it means communicating in a way that aligns with how humans actually process information. It’s about making the right choice feel like the easy choice.

Now that you know about these two systems, how might you look differently at your next campaign, your website copy, or even your product packaging?