Beyond the Suggestion Box: The Four Customer Roles That Drive True Innovation

For decades, the standard advice on innovation has been simple: listen to your customers. Businesses have been told to pay close attention to feedback and build the most requested features. This idea, along with the myth of the lone genius having a sudden “eureka!” moment, has shaped how we think new ideas are born. But that’s only part of the story, and relying on it alone is a mistake.

For decades, the standard advice on innovation has been simple: listen to your customers. Businesses have been told to pay close attention to feedback and build the most requested features. This idea, along with the myth of the lone genius having a sudden “eureka!” moment, has shaped how we think new ideas are born. But that’s only part of the story, and relying on it alone is a mistake.

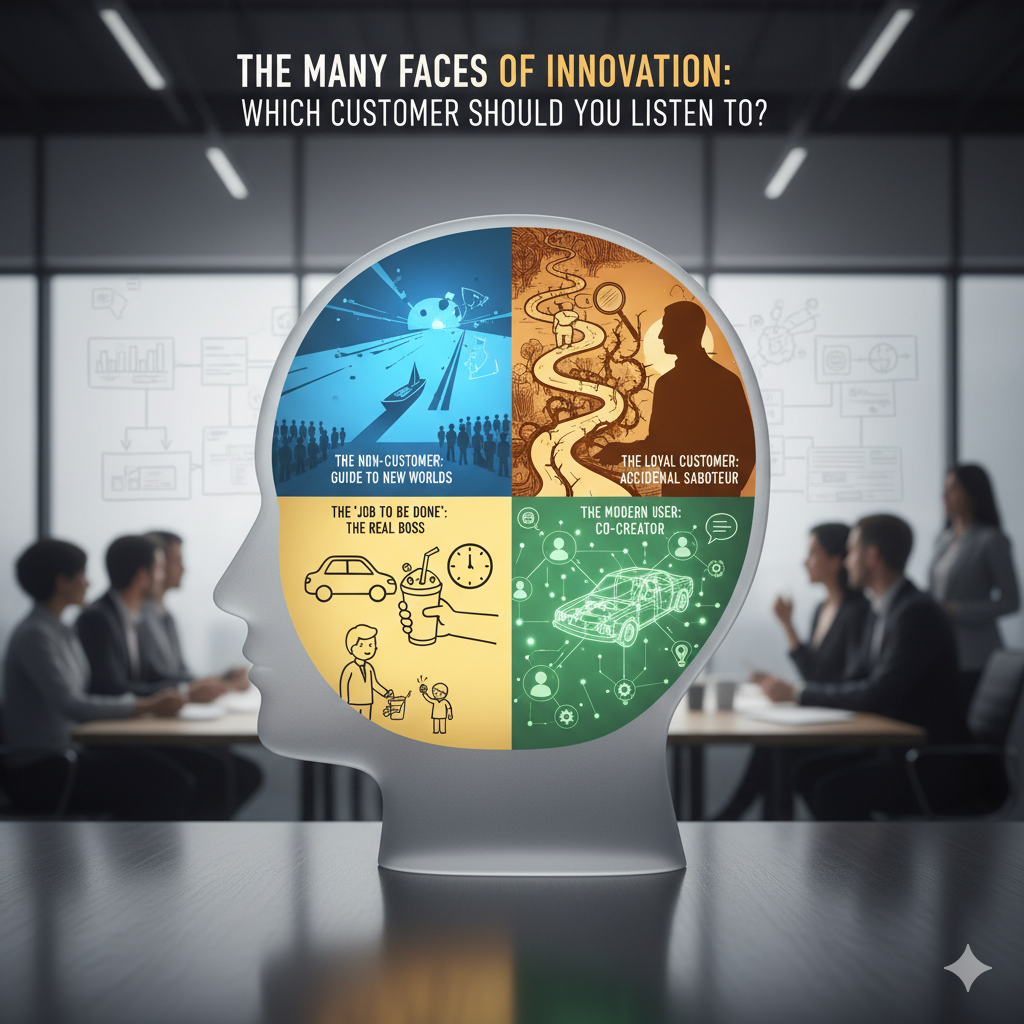

The customer’s true role in creating ground-breaking products is far more complex and interesting than a simple suggestion box can capture. Depending on the situation, the customer can be a guide to new markets, an accidental obstacle to future success, a source of deep insight, or an active partner in creation. The key isn’t whether you listen to the customer, but understanding which customer you’re listening to, and why.

This post explores four powerful roles customers play in innovation, drawing on ideas from leading business thinkers. Together, they show a spectrum of strategies—from intentionally ignoring existing customers to collaborating deeply with them. By understanding these different “faces” of the customer, innovators can move beyond small tweaks and learn how to create real breakthroughs.

1. The Guide to New Worlds: The “Non-Customer”

In their influential book Blue Ocean Strategy, W. Chan Kim and Renée Mauborgne argue that major innovations rarely come from fighting competitors over existing customers in a crowded market (a “red ocean”). Instead, they come from creating entirely new markets (“blue oceans”) by focusing on non-customers—the huge group of people who aren’t currently using what your industry offers.

Cirque du Soleil is a classic example. Instead of trying to create a better circus for traditional circus-goers, it reinvented the experience. By looking beyond the typical audience to adult theater-goers, Cirque du Soleil blended the thrill of the big top with the artistic depth of the theater. It got rid of expensive animal acts and added new elements like themes, artistic music, and a refined atmosphere. In doing so, it attracted a whole new audience that had previously been non-customers of the circus.

To make this idea practical, Kim and Mauborgne identify three types of non-customers:

- First Tier: People on the edge of your market who use your product minimally while looking for something better.

- Second Tier: People who consciously choose against your market’s offerings.

- Third Tier: “Unexplored” people in distant markets who have never been considered potential customers. By finding common needs among these groups, companies can unlock massive new demand.

To maximize the size of their blue oceans, companies need to take a reverse course. Instead of concentrating on customers, they need to look to noncustomers. And instead of focusing on customer differences, they need to build on powerful commonalities in what buyers value.

— Blue Ocean Strategy, W. Chan Kim and Renée Mauborgne

This concept is a powerful reminder to look beyond your current competition. By understanding why non-customers stay away, you can find the insights needed to create a market of your own, making the competition irrelevant.

2. The Accidental Saboteur: The Loyal Customer

It might seem strange, but the very customers who make a company successful today can sometimes lead to its failure tomorrow. This is the core idea in Clayton M. Christensen’s landmark book, The Innovator’s Dilemma. The dilemma is that successful, well-run companies often fail because they listen too closely to their best customers.

These loyal customers usually ask for sustaining innovations—making products better, faster, and more powerful in ways they already appreciate. Companies invest heavily to deliver these improvements, which keeps their profitable, mainstream customers happy. The problem is, this intense focus causes them to overlook or dismiss disruptive technologies. These new innovations might not perform well by traditional standards at first, but they offer new advantages—like being cheaper, smaller, or more convenient—that appeal to a new or ignored niche. Over time, these disruptive technologies improve until they can meet the needs of the mainstream market, pushing the old leaders aside.

The disk drive industry is a perfect example. In the early 1980s, established firms making 8-inch drives listened to their customers, who all wanted more storage capacity. Because of this, they dismissed the new 5.25-inch drives, which held far less data. But this smaller, cheaper drive was exactly what the emerging desktop computer market needed. Trapped by the demands of their existing customers, the established companies missed the shift and were overtaken by newcomers.

Blindly following the maxim that good managers should keep close to their customers can sometimes be a fatal mistake.

— The Innovator’s Dilemma, Clayton M. Christensen

The lesson isn’t to ignore your loyal customers, but to understand their limits. They can tell you how to improve what you have now, but they can’t always see what’s next.

3. The Real Boss: The “Job to Be Done”

In a later book, The Innovator’s Solution, Clayton M. Christensen offers another powerful shift in thinking: the “Jobs to Be Done” theory. The framework suggests that customers don’t just buy products; they hire them to do a specific “job.” Understanding that job is the secret to creating things people will want to buy again and again.

The famous milkshake example explains it perfectly. A fast-food chain wanted to sell more milkshakes and discovered that customers were “hiring” the milkshake for two very different jobs. The first job, for morning commuters, was to be an easy-to-handle, engaging distraction for a long, boring drive. The second job, usually in the afternoon, was for parents to give their child a quick, simple treat.

These two jobs required completely different solutions. For the morning commute, the milkshake needed to be even thicker to last longer, maybe with small chunks of fruit to make it more interesting. For the parent-and-child job, a thinner, faster-to-drink shake was better. Focusing on customer demographics (like “35-year-old male”) was useless; focusing on the “job to be done” showed the path to real improvement. This switch is a game-changer because it shifts the focus from who the customer is to what they are trying to accomplish, revealing the true motivations behind their choices.

4. The Co-Creator: The Modern User

In our connected world, customers are no longer just passive buyers. They’ve become active partners in creation. This collaboration happens across the entire innovation process—from spotting needs to funding, designing, testing, and refining the final product. Companies aren’t just building things in secret labs anymore; they’re engaging users every step of the way.

- Observing Unspoken Needs: As Tim Brown explains in Change by Design, “design thinking” involves deep empathy to find users' latent needs—deep-seated problems they might not even know how to describe. Innovators go out into the world to see how people actually behave, uncovering opportunities that surveys would miss.

- Funding and Designing: Once a need is identified, the public can be involved as co-funders and co-designers. In Exponential Organizations, Salim Ismail explains how companies like Gustin use crowdfunding to let customers fund jean designs before they are made, eliminating risk. Meanwhile, Local Motors crowdsources the design of its vehicles from a global community.

- Prototyping in Public: This teamwork extends to testing. Before building a single hotel, Starwood Hotels built a virtual prototype of its Aloft hotel in the online world of Second Life. As described in Change by Design, thousands of potential customers explored the virtual hotel and gave feedback on everything from room layout to lobby colors, which had a huge impact on the final design.

- Driving Constant Improvement: This partnership doesn’t stop at launch. The “Build-Measure-Learn” feedback loop from Eric Ries’s The Lean Startup is the playbook for modern innovation. Startups release a minimum viable product (MVP), measure how customers react, and learn what to build or change next. This makes the customer an essential partner in a non-stop cycle of improvement.

Companies are ceding control and coming to see their customers not as “end users” but rather as participants in a two-way process.

— Change by Design, Tim Brown

This collaborative approach is the new frontier. It turns product development from a one-way street into a continuous conversation, ensuring that what gets built is not just what customers want, but what they helped create.

Conclusion: Who Are You Listening To?

The customer is not a single entity. In the world of innovation, they wear many faces: the non-customer pointing you to new markets, the loyal customer who can accidentally keep you stuck, the “job” that reveals what people really want, and the modern user who helps you build the future.

Successful innovation depends on knowing how to balance all these roles. A smart company might listen to its loyal customers to improve its main product, while also exploring non-customers to create its next big thing. It might use the “Jobs to Be Done” framework to refine a new idea, while also building a community of co-creators to guide its evolution. The key is not just to listen, but to understand which customer to listen to, for what purpose, and at what time.

So, the next time you use a product, ask yourself: what ‘job’ did you really hire it to do?